Source: Beard Bros Media01/13/2026

Cannabis Education, Culture, News 2026

More than fifty years before today’s debates over rescheduling cannabis, the United States government already had its answer. Not a theory. Not an activist argument. A federally commissioned, taxpayer-funded, bipartisan conclusion.

Cannabis was not a major public health threat. It showed legitimate medicinal potential. Criminalizing its use caused more harm than the substance itself.

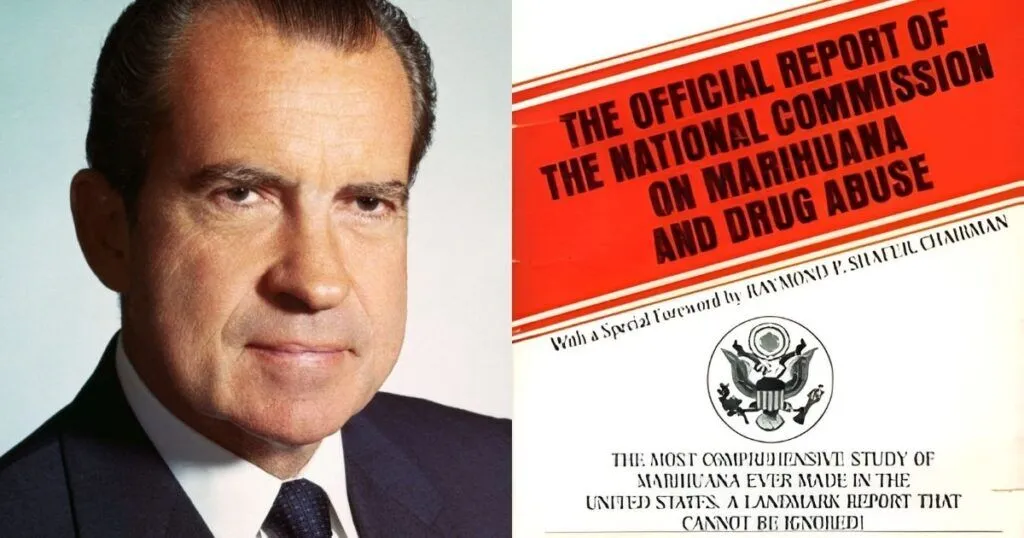

That conclusion came from the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, better known as the Shafer Commission, created by President Richard Nixon in 1969. The irony is brutal: the modern War on Drugs was launched not because science demanded it, but because science got in the way.

Understanding the Shafer Commission is essential to understanding why today’s rescheduling proposals fall short—and why descheduling cannabis entirely is the only policy position consistent with evidence, history, and honesty.

The Political Moment That Produced the Shafer Commission

By the end of the 1960s, cannabis use had become widespread across college campuses, creative communities, and anti-war movements. Arrests for marijuana possession were skyrocketing, public opinion was fracturing, and states were struggling to justify severe penalties for a substance that many Americans saw as relatively benign.

Richard Nixon ran on a “law and order” platform that framed social unrest as a criminal problem rather than a political one. Cannabis quickly became a convenient symbol of disorder. Still, Nixon needed legitimacy. He needed data. He needed a report he could point to as justification for expanding federal drug enforcement.

Congress responded by authorizing the creation of a national commission to study marijuana objectively. Nixon appointed Raymond Shafer, a conservative former governor, to lead it. The panel was deliberately stacked with professionals from medicine, law enforcement, education, psychiatry, and the judiciary. This was not a counterculture exercise. It was meant to confirm prohibition, not challenge it.

What followed was one of the most comprehensive marijuana studies ever conducted by the federal government.

What the Commission Actually Studied

Over two years, the Shafer Commission examined marijuana from every angle available at the time. The team examined existing medical literature, conducted sociological research, and evaluated arrest data while analyzing patterns of use. Their studies focused on cannabis’s impact on cognition, motivation, physical health, mental health, and social behavior.

They also examined enforcement itself—how marijuana laws were applied, who was being arrested, and what consequences those arrests carried.

This distinction matters. The commission did not limit its scope to pharmacology. It treated cannabis as a social issue shaped as much by law as by chemistry.

That broader lens is exactly what today’s rescheduling debate often lacks.

The Commission’s Conclusions Were Clear—and Damning

When the commission published its final report in 1972, it did not resemble the alarmist rhetoric dominating political speeches at the time. Instead, it was measured, conservative, and deeply inconvenient.

The report found that marijuana use did not lead to physical dependence and did not cause violent behavior. It did not function as a gateway to harder drugs in any meaningful causal sense. The majority of users did not escalate their use, withdraw from society, or suffer significant long-term harm.

Importantly, the commission directly compared marijuana to alcohol and concluded that cannabis posed less risk to both the individual and society. That comparison alone undermined decades of propaganda.

The report also addressed medicine. Even with limited research tools and heavy federal restrictions, the commission acknowledged that cannabis demonstrated therapeutic value. It cited evidence for pain relief, appetite stimulation, and relief from nausea, and emphasized the need for expanded medical research rather than suppression.

Most critically, the commission concluded that criminal penalties for marijuana possession were disproportionate and unjustified. Arrests, it found, caused lasting harm to individuals without producing meaningful public benefit. The law itself was creating the damage.

The Recommendation That Still Haunts Federal Policy

The commission’s core policy recommendation was simple: remove criminal penalties for possession of marijuana for personal use. Adults using cannabis privately, it argued, should not face arrest, incarceration, or lifelong consequences.

This recommendation did not call for commercial legalization or unregulated markets. It was a narrow, cautious proposal rooted in harm reduction and respect for personal liberty.

For Nixon, it was unacceptable.

Nixon’s Rejection of His Own Science

Nixon never seriously considered implementing the Shafer Commission’s recommendations. White House recordings later revealed that he viewed marijuana through a deeply moralistic and political lens. He associated cannabis with anti-war protestors, Black Americans, and what he saw as a breakdown of traditional authority.

In Nixon’s worldview, marijuana was not a health issue to be understood but a cultural threat to be crushed.

Rather than engage with the report, the administration sidelined it and moved forward with the Controlled Substances Act, classifying cannabis as a Schedule I substance—defined as having no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.

This classification was not based on the Shafer Commission’s findings. It directly contradicted them.

That contradiction is the foundation of today’s policy crisis.

The War on Drugs Was a Political Strategy, Not a Scientific One

Years later, Nixon administration officials would openly admit what the Shafer Commission already implied. Cannabis prohibition was never about public health.

John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic policy advisor, explained that the War on Drugs was designed to criminalize political enemies by proxy. By associating marijuana with anti-war activists and Black communities, the administration could justify surveillance, arrests, and disruption without explicitly targeting protected political or racial identities.

In that context, the Shafer Commission was dangerous. It stripped away the moral justification for repression. It proved that the threat was exaggerated—and that the harm came from enforcement, not use.

So it was buried.

How This History Directly Shapes Today’s Rescheduling Debate

Fast forward to the present, and the federal government finds itself in an uncomfortable position. Medical cannabis is legal in most states. Adult-use legalization continues to expand. Scientific research now overwhelmingly supports cannabis’ therapeutic value.

Yet cannabis remains federally illegal.

The proposed solution currently on the table is rescheduling, typically framed as moving cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III. This is often presented as progress, but history tells us to be skeptical.

Rescheduling still treats cannabis as a controlled substance that requires federal permission to exist. It maintains criminalization outside tightly regulated channels while keeping federal agencies in charge of access, research, and commerce. This approach enables the government to quietly sidestep accountability for decades of harm by framing the issue as nothing more than a classification error.

The Shafer Commission proves otherwise.

The issue was never scheduling. It was criminalization itself.

Why Descheduling Aligns With the Shafer Commission—and Rescheduling Does Not

The Shafer Commission did not argue for softer enforcement. It argued for removing marijuana from the criminal system entirely. That philosophy aligns directly with descheduling, not rescheduling.

Descheduling acknowledges that cannabis does not belong in the same regulatory framework as dangerous narcotics. It allows states to regulate cannabis like alcohol, supports medical access without federal obstruction, enables robust research, and removes the legal justification for ongoing arrests and surveillance.

Rescheduling, by contrast, keeps the federal government in a gatekeeping role it has historically abused. It does not repair the damage caused by decades of enforcement. It simply repackages prohibition in medical language.

From a historical standpoint, rescheduling is not reform—it is delay.

The Cost of Ignoring the Shafer Commission, Then and Now

Because Nixon ignored the Shafer Commission, millions of people were arrested, incarcerated, and stigmatized. Medical research was suppressed for generations. Entire communities were destabilized. Trust in public institutions eroded.

Today, rescheduling risks repeating that mistake by prioritizing political optics over structural change.

The lesson of the Shafer Commission is not subtle. When science conflicts with power, power will lie unless forced to change.

The Truth Is Already on the Record

The United States does not lack evidence on cannabis. It lacks political courage.

The Shafer Commission told the truth in 1972. Modern science has confirmed it repeatedly. The only question left is whether policymakers are willing to confront the legacy of deliberate misinformation—or whether they will continue to tinker around the edges while maintaining control.

Descheduling is not radical. It is the overdue implementation of conclusions reached more than half a century ago.

The report was buried. The truth wasn’t.

And it’s still waiting to be acted on.